How Did It All Go Wrong?

The advertising industry's Golden Age had prestige, success, profitability, and belief in the inherent value of creativity. There was magic in creativity. It was the only thing that mattered.

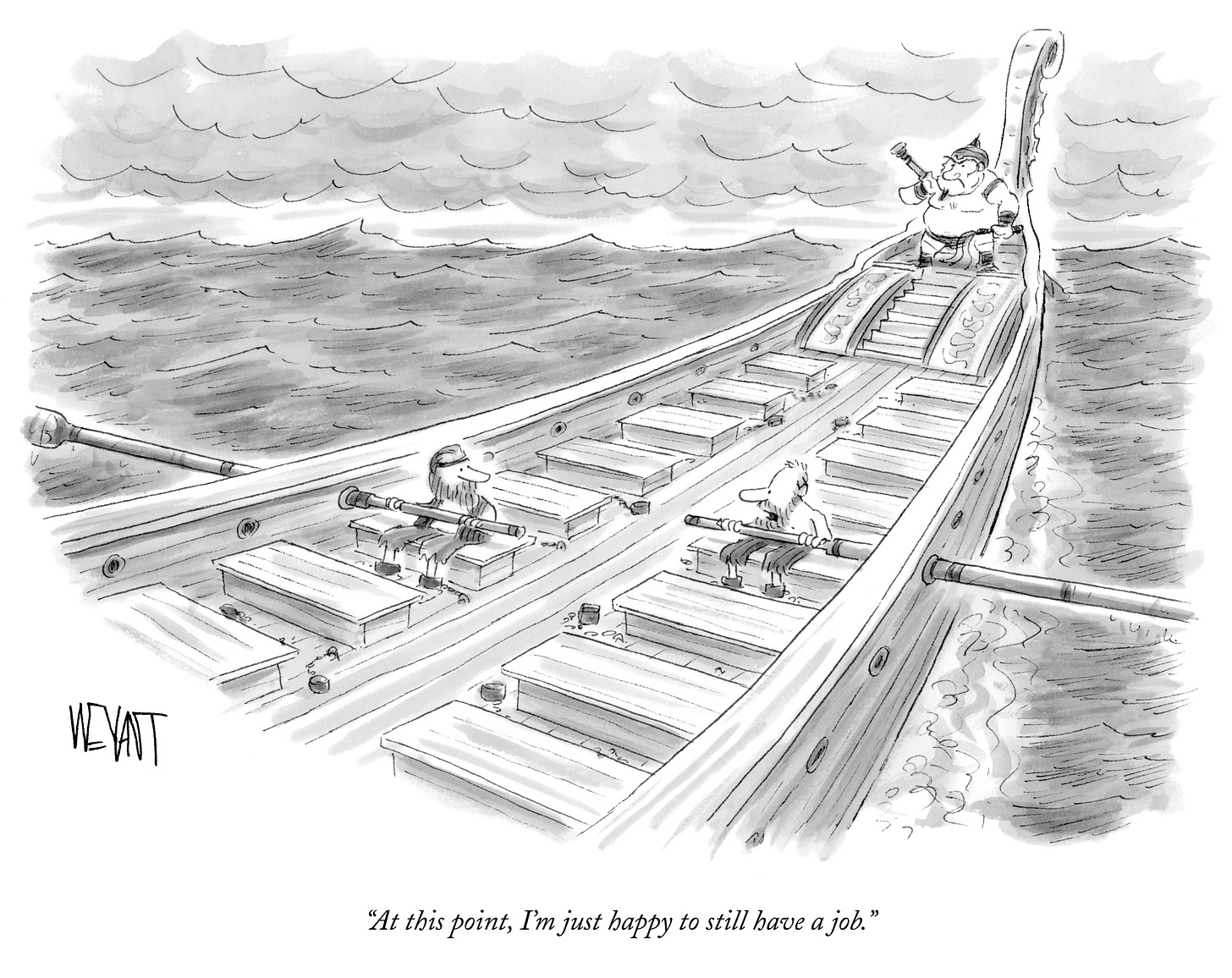

Credit: Christopher Weyant, The New Yorker, The Cartoon Bank

Back in the day, under the 15% media commission system, income took care of itself. Agencies had more than enough income to fund operations and still show impressive profits. There was so much income that potential profitability had to be disguised. Agencies doubled staffing, paid lavish salaries and bonuses, entertained clients and had expensive fun, convinced it was their due reward for being creative.

Bill Bernbach proved the value of creativity with “Think Small” for VW. Think Small became the industry’s most profitable idea, creating a religion of creativity. There was no need to worry about anything else.

High expenses reduced profit margins to “normal” levels, but agencies could still afford to focus on The Work, The Work, The Work. Rework was a virtue. Great ads ran over and over, generating new 15% commissions each time they ran. Successful creative work drove agency revenue.

There were no procurement executives, no complicated scopes of work, no benchmarks, no search or benchmarking consultants.

What mattered? Having Client Service executives motivate clients to spend more on media. Agency “suits” sold the media message to their clients:

The more money you spend on media, the more creative work we will do, and the faster your brands will grow.

We can prove it. Here’s the data.

It all began to go wrong when commissions disappeared, and agencies were paid for man-hours. Man-hour billing changed everything. The media salesmanship by agency suits disappeared.

Nothing replaced it. Creativity remained, but the financial wind that filled agency sails disappeared.

Clients, overwhelmed about how to manage man-hour billing, asked: What’s an appropriate fee? How many people do agencies need? What’s a fair overhead?

Marketing brought in Procurement to figure it out. Procurement brought in the benchmarkers.

Agencies dismissed Procurement as spreadsheet jockeys who didn’t understand creativity.

Procurement struck back, viewing agencies as overpaid prima donnas in need of discipline. Fee cuts would teach them a lesson.

The Holding Companies. In 1985, Martin Sorrell founded WPP, soon buying JWT and Ogilvy. He knew that agencies were fat, and he established the practice of routine cost-reductions to widen agency margins and drive WPP’s share price upwards.

Agencies found themselves caught between fee-cutting clients and their profit-hungry holding company owners.

Scopes of work determined FTEs, yet few agencies measured their scopes. They focused on creativity, remembering that Bill Bernbach said “No one remembers the number of ads you ran. They remember the impression you made.”

Agencies continued to believe that creativity solved all problems. There was no C-Suite vision for measuring or managing scopes. Instead, agencies cut headcounts to make margins, desensitized to the human and talent cost of this self-defeating practice.

Unfortunately, financial incentives for “making the numbers” replaced empathy for employees.

Agencies failed to see that man-hour billing required them to understand and measure their workloads. They still do not document or measure their workloads, even as AI prepares to devour man-hours and fees.

Shrinking headcounts and expanding workloads. By 2004, surplus headcounts were gone. Downsizing continued, nonetheless, pushing creative staffing below the levels needed to deliver high-quality work.

From 2004 onward, digital and social workloads exploded. Declining fees from Procurement met rising scope demands from Marketing, a double-whammy that hit both media and creative agencies. Accelerated downsizing continued as the default survival tactic.

Loss of AOR status. Creative agencies viewed digital and social as software work, alien to their creative cultures, and they were reluctant to diversify. They stayed with TV, print, radio and direct marketing, unwilling to diversify into “software” until too late. They finally diversified into website development, search, banner ads, email marketing and the rest, but the damage was done. They already lost AOR status, with clients hiring separate shops for digital work.

Holding Company Relationships. Sorrell observed the agencies’ early digital distain, writing in WPP’s 2003 annual report that specialized skills thrive best in specialist companies. This seemed to justify agency behavior, but Sorrell used the phenomenon to provide a rationale for holding-company relationships. These relationships increased holding company power, but they tended to marginalize the individual agencies.

**************************************************

With the disappearance of AORs, Procurement now viewed agencies as replaceable vendors, subject to contracts and constant reviews. Agency relationships became transactional.

This forced agencies into becoming perpetual new-business machines, constantly having to replace lost clients. With pitch costs rising as high as $1 million each, new business became a financial burden. More aggressive cost reductions were required.

Creative agencies had no fallback strategy. They simply had to engage in and win more pitches, often by offering very low fees.

Media agencies, by contrast, had a fallback strategy: principal-based media buying, generating margins through inventory arbitrage and other non-transparent practices.

Even so, holding-company performance eroded.

The Endgame. Weakened holding-company results led to brand mergers and, finally, the Hail Mary of Hail Mary’s, the Omnicom acquisition of IPG, John Wren’s strategy to increase principal-based media and cut $750 million from agency costs.

Nowhere yet has any C-Suite leader proposed a program to help its agencies transform to be “paid for outputs” for the growing, fragmented, and complex media and creative deliverables that now define modern marketing.

AI looms as a man-hour killer.

Stay tuned for the final chapter. It can’t be long in coming.

A comprehensive history! This is good stuff.